Identifying

and understanding important individual investors can help corporate executives

predict the direction of share prices.

Kevin P.

Coyne and Jonathan W. Witter

The

McKinsey Quarterly, 2002 Number 2

CEOs always want to know how the market

will react to new strategies and other major decisions. Will a company’s

shareholders agree with a particular move, or will they fail to understand the

motives behind it and punish the stock accordingly? And what can management do

to improve the outcome?

Trying to

predict stock price movements is necessary, of course. After all, when stock

prices fall, the cost of borrowing and of issuing new equity can rise, and

falling stock prices can both undercut the confidence of employees and

customers and handicap mergers. Unfortunately, however, most of these

predictions are no more than rough guesses, because the tools CEOs use to make

them are not very accurate. Net present value (NPV) may be useful for

estimating the long-term intrinsic value of shares, but it is famously

unreliable for predicting their price over the next few quarters. Conversations

with sample groups of investors and analysts, conducted by the company or by

investment bankers, are no more reliable for gauging market reactions.

But executives can dramatically improve the accuracy of

their predictions. By adopting a more systematic, rigorous approach, corporate

leaders can learn to understand individual investors as thoroughly as many

companies now understand each of their top commercial customers. It is possible

to know such customers well because there are only so many of them. Equally,

only a finite number of investors really matter when it comes to predicting

stock price movements.

Every CEO knows

that when buyers are more anxious to buy than sellers are to sell, share prices

rise—and that they fall when the reverse happens. But fewer CEOs know that not

every buyer or seller matters in this equation. Our research on the changing

stock prices of more than 50 large US and European listed companies over two

years1 makes it clear that a maximum of only

100 current and potential investors significantly influence the share prices of

most large companies. By identifying these critical individual investors and

understanding what motivates them, executives can predict how they will react

to announcements—and more accurately estimate the direction of stock prices.

Armed with these

new and solid insights about how critical investors behave in specific

situations, executives can make strategic decisions in a different light.

Knowing what makes crucial investors buy, sell, or hold the company’s stock

allows CEOs to calculate what its share price might be after an announcement

and to factor this calculation into their strategic and operating decisions. To

head off short-term selling, a company could manage the timing, pace, or

sequencing of strategic announcements. It could introduce a new management team

before announcing an acquisition. It could also test an important new product

in selected markets before the nationwide rollout. How will investors react to

a merger announcement and what will the resulting share price mean for a deal?

How might a spin-off fare in the market? Does the company need to prepare the

market or to consider a carve-out instead?

A CEO even has

the choice of forging ahead in the face of adverse predictions, using the

information to manage the expectations of the board. An executive may, for

instance, consider bold strategies even though they could push some critical

investors to sell the company’s stock.

The few

that matter

It should come

as no surprise that big trades can significantly move the needle on a company’s

stock price. When the Bass family of Texas, for example, sold its stake in

Disney, in September 2001, in response to a margin call, Disney’s stock fell by

8 percent.

But typically,

short-term changes in a company’s stock price aren’t the result of a single big

trade. For the 50 companies whose quarterly stock price variations we studied,

we consistently found that the majority of unique changes in each company’s

stock price resulted from the net purchases and sales of the stock by a limited

number of investors who traded in large quantities. (By "unique

changes," we mean those occurring relative to the rest of the market. In

other words, they do not include price bumps or falls that coincided with the

overall movements of the market or the sector.)

Although the

number of crucial investors in a company ranged from as few as 30 to (more

typically) as many as 100, in each case this set of actors had a dramatic

impact on share prices. In the companies we studied, we could attribute from 60

to 80 percent of all unique changes, quarter by quarter, to the net trading

imbalances of these investors.

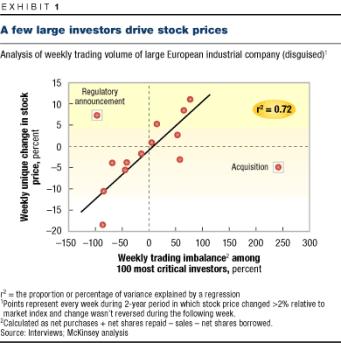

Consider a

snapshot of the trading in the shares of a large European industrial company.

Exhibit 1 shows the relationship, over a period of two years, between the net

buying and selling of its 100 most critical investors, captured weekly, as well

as the fluctuation in its stock price relative to the market index.2 In 11 of the 14 cases in which the

company’s stock price moved significantly, the price went up or down in concert

with the net buying or selling of these very investors.

The two strong

outliers in the exhibit were not random events. The point at the bottom right

occurred when the company announced the acquisition of a major competitor—a

move that large traders applauded by purchasing more of the company’s stock but

that analysts, small institutions, and retail shareholders rejected. The top

left outlier occurred when the government made a crucial regulatory

announcement whose impact appeared, on the surface, to be positive, thus

attracting a large number of smaller investors, but was actually neutral to

negative, something the largest investors understood.3

Why should the size

of the imbalance between asks and bids matter? At any instant, the market

consists of a series of graduated offers to buy (in other words, A has an

outstanding offer to buy 1,000 shares at $60, and B offers to buy 2,000 shares

at $59.875) as well as a similar set of offers to sell (C offers to sell 1,500

shares at $60.50, and D offers to sell 1,000 shares at $60.75). A sale is made

only when one side surrenders across this bid-ask spread (that is, A agrees to

buy 1,000 of C’s shares at $60.50). When buyers collectively want large amounts

of a stock, they have to keep surrendering to successive layers of sellers up

the offer curve. Sellers who unload large numbers of shares move along the

curve in the opposite direction.

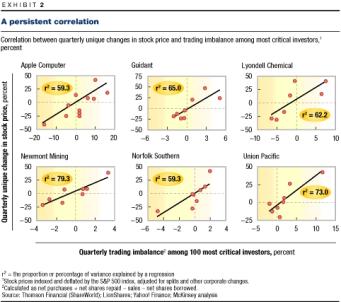

Of course, the

correlation between the buying or selling of large investors, on the one hand,

and the price of a stock, on the other, can never be perfect. Smaller investors

sometimes act in sync and overpower larger holders—as happened twice in two

years with the shares of the European industrial company. News, rumors, and

world events can spark broad market swings. But among the companies we have

studied, the correlation is remarkably persistent (Exhibit 2).

Industrial

marketing for investors

Few companies

today get to know their top investors well enough to predict with any accuracy

what will make those investors buy or sell more of their shares. The CFO of a

large financial company, which was about to announce the divestiture of a major

division, believed that he was "right on top of [our] investor base."

Indeed, in a general way, the company’s executives knew the big investors

well—what they thought of management, the creditworthiness of the company, and

so on. But executives didn’t know what investors thought about specific potential

strategies, such as a divestiture. Was the offer price that executives were

considering above or below the value investors attributed to the unit when

those investors calculated the company’s total value? Or did investors think

that the company benefited from cross-divisional synergies that would end with

the divestiture?

To develop the

ability to make predictions about shareholders, companies should identify their

stock price movers and calculate how many additional shares would be offered or

sought in reaction to specific announcements. Through background analysis and

interviews, the companies must then analyze in depth the trading behavior of

these movers, developing trading profiles for each of them. Finally, companies

should use the information in the profiles to predict which movers would be

likely to react to specific corporate announcements by selling or buying in the

short term and then calculate what this would mean for share prices.4

Getting to know

investors isn’t a one-shot process. Companies must continually reexamine who is

moving their shares—investors come and go. An ongoing dialogue with the movers

deepens the knowledge of these companies and, over time, sharpens their ability

to predict the actions of their critical investors. However, most companies

will need to beef up their investor relations capabilities to get the job done.

The good news: getting started isn’t a mammoth task. Two to three months should

be enough to develop an initial set of profiles of the most important investors.

Identify

the critical investors

A company should

begin its assessment by asking who has the potential to move its stock price.

Some of the movers could be among the company’s largest current shareholders.

Some may be smaller holders who want to increase their ownership. And some are

potential large players who do not yet own any of the company’s stock but could

purchase or short it in large quantities. What do these movers have in common?

They are active stock-portfolio managers who regularly buy and sell large

quantities of shares in the company or in similar companies—typically, managers

of mutual, pension, or hedge funds or even individual large investors.

In other words,

investors who count have both weight and a propensity to throw it around.

Although the actual calculations needed to put together the list of movers are

complicated—requiring more discussion than we can present in this article—a

likely mover is someone who does or could reasonably account for at least 1

percent of a stock’s trading volume for one quarter.

Movers are not

necessarily a company’s largest investors. Shareholders (such as family

holdings or trusts) that have owned big blocks of the company’s stock for a

long time don’t move it quarter to quarter. Neither do index funds unless the

company is added to or dropped from an important index (or unless the fund’s

assets change dramatically). Among the largest 20 investors of one big

pharmaceuticals company we studied, only 10 were movers, and this proved to be

typical of the companies we studied. What is more, nearly half of the large

movers of the stock of the pharmaceuticals company over eight quarters from

1999 to 2001 weren’t listed among its 20 largest investors during any single

quarter.

Moreover,

companies should add potential investors to the list of movers. For a large chemical business in

our study, we analyzed the way the positions of investors in other chemical

businesses changed over time. One investor, a $22 billion investment fund, had

been an active trader in other, similar chemical companies and liked to buy

assets at the bottom of a cycle. At the time, the sector was depressed, so for

this and other reasons we added the investor to the company’s list of movers. A

few months later, the investor purchased more than five million of the

company’s shares.

Potential movers

include those who have made money investing in other industries in similar

circumstances. Investors who bet on the right players in an industry that

consolidated, for example, may now be eyeing investments in other sectors on

the verge of consolidation. Potential movers may also be investors who

purchased shares in a company’s upstream or downstream suppliers and have a

history of investing more broadly in the value chain. Some may have a taste for

betting on companies that use certain capital models (high cash flow, say, or

high leverage), have new CEOs, or face particular market changes or competitive

conditions.

To determine how

many investors should go on the list—40? 70? 100?—a company should test the

accuracy of its predictions over previous quarters to arrive at the number that

works best. Too few will yield poor correlations between activity and stock

prices; too many will add to the cost and complexity of the process. In

addition, the list changes frequently. Our experience suggests that a mover

typically stays on such lists for six quarters—long enough to give the company

time to become familiar with it but short enough so that there will always be

new movers to study.

Moving

the movers

Once a company

has identified its movers, the next step is to develop thorough profiles of all

of them. Companies begin by conducting an "outside-in" analysis of

each one, including its stated investment criteria and objectives and its

trading patterns. Discussions with every investor give a company a chance to

fill in the gaps in its understanding of its movers and to confirm its

hypotheses about what they trade and why.

The resulting

profile should first describe how an investor makes decisions. What does the

investor want to invest in, using what valuation methodologies? How is it

likely to react to events or to data, which after all can be interpreted in

many ways? Are its investments subject to any constraints, such as their size

and frequency? Second, the profile should describe each investor’s views on

issues that the company might face—such as any new strategies (for instance,

whether the company should go into China), earnings surprises, and changes in

management.

To get this kind

of information, companies must phrase the questions carefully in view of a US

Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) regulation that prohibits companies

from disclosing material information to some but not all investors.5 Typically, indirect questions work best.

A company might ask investors why they purchased or sold their holdings in a

particular business, for instance. But the company would actually be trying to

understand why they sold their holdings after the business announced, for

example, that it was investing in China. Do the investors dislike the risks

that are associated with China, distrust the management team put in place to

manage expansion in Asia, or reject specific details of the disclosed plan?

The precise

format of the profiles will vary from company to company, depending upon the

decisions and events it expects to face. However, the content of each profile

should focus on predicting how each investor will react to specific corporate

events (Exhibit 3). Companies will want to collect the information in a

database where it can be updated regularly.

Making

predictions

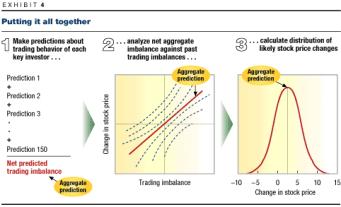

With the movers

identified and profiled, the investor relations staff and executives can make

reasonable judgments about who will sell, buy, and hold. This process isn’t

merely a mathematical exercise, though it does involve many calculations.

Besides

assessing whether each investor will approve or disapprove of a given

announcement, executives must estimate how many shares the investor is likely

to buy or sell. They can be guided in these estimates by such details as the

average trade the investor makes and whether the investor historically

"bleeds" (buys and sells incrementally over time) or

"blasts" (buys and sells quickly and in large blocks).

This information

gives the company an idea of the extent of the trading imbalance that will

likely occur as a result of the announcement. Executives, guided by past

imbalances in the company’s stock and the way they moved prices, can use this

estimate to make a rough assessment of how the stock price will react (Exhibit

4). Secondary, or knock-on, events should also be considered: if the stock

price goes up or down, for example, what might momentum players do? This too

can be derived from past patterns.

Although the

process itself is straightforward, making these predictions can be quite

complex. Nonetheless, several companies we have worked with have done the

necessary calculations and used the information to guide their strategic

decisions. One company, recognizing that it would take a hit, decided that it

could do little about this except to prepare and manage its board. (In this

case, estimates of what would happen to the stock price were extraordinarily

accurate.) Another company decided to postpone a restructuring when it realized

how far its stock price was likely to fall. In a third case, two companies were

about to announce that they were merging. But the estimated dip in the

acquirer’s stock price after the announcement could have affected the deal (an

equity and cash buy), so executives at the two companies used the profiles to

identify investors who should be reached immediately and individually.

Profiling also helped the companies tailor their communications to those

investors.

Even if no

immediate decisions are pending, a company should try to predict probable moves

by investors on a quarterly basis if not more often. Accuracy improves with

practice.

Building

the capabilities

Companies that

choose to adopt an industrial-marketing approach to investor relations will

need to make at least two key changes. The first is to stop viewing the market

as a monolithic entity that is judging a company’s performance in an

adversarial way. When the company’s stock price changes, executives shouldn’t

ask why the market moved; they should pinpoint who bought, who sold, and why.

In fact, managers should view investors much as managers in private companies

view their corporate owners—and understand them just as well.

Second,

companies will need to overhaul their investor relations units. In the vast

majority of companies today, the investor relations function is largely

administrative: it oversees the production, but not always the content, of

regulatory and annual reports; it administers the registry of shareholders and

sets up investor road shows, visits by analysts, and conferences; and it talks

to shareholders—when they call.

Instead, the

investor relations unit will have to take on a more strategic role, almost as

an adjunct to strategic planning. It will be responsible for managing the

key-account process to identify movers and understand their behavior. Its staff

will have to test all major plans and announcements for their effect on the

price of the company’s shares and suggest modifications to those plans to bring

them into better alignment with the views of key shareholders. Indeed, for the

first time, the investor relations unit will become an important adviser to the

CEO.

But this

approach calls for investor relations leaders who can stand up to the CEO and

deliver bad news when necessary. They will also have to be capable of handling

tough interviews with investors who are pressing them for information they

cannot divulge under SEC regulations or for competitive reasons. Sharp, independent,

and analytical investor relations directors may emerge from the ranks of

business development, strategic planning, or even, in some instances, internal

auditing.

------------------------------------------------------------------------

Taking a more

rigorous, structured approach to investor relations and stock price predictions

clearly requires resources, including the time and attention of senior

management. But given the importance of share prices, why would a CEO ever want

to be left guessing?