In the fall of 2005, when Texas Pacific Group and Warburg Pincus LLC bought luxury retailer Neiman Marcus Group Inc., Jim Coulter, TPG's co-founder, was nervous, said people familiar with the deal. What if there was another terrorist attack or a sharp economic downturn? What if Neiman's management got fashion trends all wrong?

To protect against an unexpected turn, TPG came up with an unusual structure

for some of the debt it put on Neiman Marcus to help pay for the purchase.

If the retailer experienced unexpected head winds, it could stop paying cash

interest on $700 million in debt, and instead agree to pay back much more when

the bonds mature in 2015.

"If the company hits a speed bump, it gives it liquidity and a cushion," said Kewsong Lee, a partner at Warburg Pincus who worked on the deal. "This innovation was one factor enabling us to pay a more aggressive price."

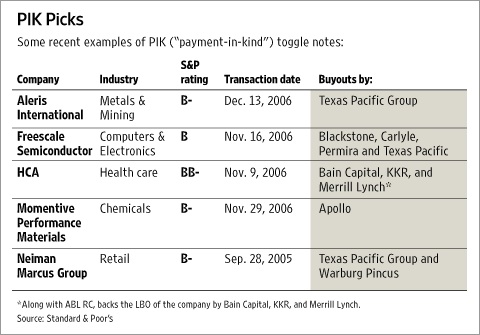

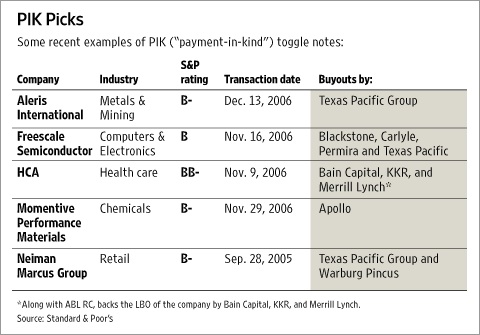

The bond, formally known as a payment-in-kind toggle note, is becoming an increasingly important part of the arsenal of private-equity firms as they pile debt on their corporate trophies.

These "PIK toggle" securities allow borrowers to make a choice. They can keep paying interest on a bond, or they can defer paying interest until the bond matures, and in the process agree to pay an interest rate that is effectively higher. In the case of Neiman Marcus, the interest rate on its debt with this feature will rise from 9% to 9.75% if it decides to defer payments, which it hasn't done.

The increased use of these bonds is one of the latest examples of the easy lending terms that dominate the corporate borrowing market these days and have helped fuel the historic buyout boom. It also is a sign the boom could keep going for some time.

Corporate default rates are at record lows less than 1%. That has investors clamoring for corporate bonds and loans, because they don't seem very risky. In 2006, companies issued $624 billion in speculative grade bonds and loans, up from $389 billion in 2005.

Easy lending terms such as those of PIK-toggle bonds make it possible for even companies with strained cash flows to stay afloat longer than they otherwise would by putting off interest payments. The downside is that borrowers and investors in the end could find they have even more debt than expected if the credit cycle turns.

"Cheap debt is the rocket fuel," said Bill Conway, a co-founder of Carlyle Group, at a January conference. "We try to get as much as we can as cheaply as we can and as flexibly as we can."

The health of the debt market matters hugely to private-equity firms, which have used massive dollops of debt to go after ever larger prey and reap higher returns on their investments. Nearly every TPG deal since Neiman Marcus includes debt with the PIK toggle feature. All the megadeals, including Freescale Semiconductor Inc., HCA Inc. and ballpark-concessionaire Aramark Corp. do as well.

A similar feature that allowed companies to defer interest payments was popular

during the late 1980s buyout boom, but fell out of favor in the 1990s.

Although default rates are low, and easy lending terms make it easier to stay solvent, the credit quality of some companies show some signs of deteriorating. Some 30% of companies issuing debt in 2006 carry "junk" credit ratings of "B plus" or below, compared with 7% in 2002, according to Standard & Poor's Leveraged Commentary & Data group. In many cases, the debt itself isn't going to fund new investments; rather it is used to finance takeovers or to pay new owners a special dividend.

Many companies have been able to issue debt without the usual terms, known as covenants, that require them to meet certain performance metrics to avoid defaulting. Last year, there was about $24 billion in such debt, ten times the amount in 2005.

This is another factor that is making it easier for companies to avoid defaulting. In the past, when companies fell short of financial performance targets, "banks would take over the company at the worst possible time or we would have to put more money in," said Tony James, president of Blackstone Group at a conference at Harvard Business School. "Now we can live to fight another day."

To many analysts, such "covenant lite" loans or PIK toggle notes are glaring signs of the bull market in debt, and underscore the power of bond issuers at a time when investors are flush with cash and willing to take chances for high returns. Some bond issuers said the new features are in the interest of investors, because the features help companies avoid default and complex bankruptcy proceedings. Proponents have said the high interest rates attached to PIK toggle notes give borrowers an incentive to keep making interest payments unless times turn dire.

Others are less sure. S&P's Leveraged Commentary & Data Group noted in a commentary, for example, that PIK toggle bonds could be risky because they have the potential to saddle investors with more debt in companies and less cash from them just as the companies are beginning to struggle.

"Because there is so much cash around, lenders are being pushed to give up more and more," said Howard Gellis, who runs the debt capital markets group at Blackstone Group.

So far this cycle, none of the issuers have taken advantage of their option and ceased paying interest. It remains unclear how investors will react if companies do start exercising this right.

"Since the message is that a company can't afford to pay cash, it is hard to see how the market won't be spooked," said Steven Shapiro, a partner at GoldenTree Asset Management, which has $6 billion to invest out of its hedge-fund operations. "For the most part we don't invest in them."

Write to Henny Sender at henny.sender@wsj.com