By ANN GRIMES

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

May 27, 2004; Page C1

Venture-capital firms can make a lot of money for pension funds and colleges.

Just don't ask them how they do it.

Bent on keeping their holdings and performance results confidential, venture-capital funds have successfully lobbied to amend several states' open-records laws so that public pension funds and university endowments can refuse to disclose key details about their investments.

The funds, which pool money from wealthy people and deep-pocketed institutions to invest in start-up companies, argue that they are trying to protect trade secrets for competitive reasons. Government watchdogs and press groups are alarmed by the trend, arguing that the restrictions will make it harder to hold government officials accountable for how they invest public money. And industry critics say venture capitalists are mainly trying to keep embarrassing investment flops under wraps.

Legislatures in some states are acting under duress. After Sequoia Capital

barred the University of Michigan from future investments in its funds because

they would be open to public scrutiny, Gov. Jennifer Granholm last month signed

a bill to exempt certain investment data from public disclosure. In March,

Colorado Gov. Bill Owens signed a similar bill at the urging of local venture

capitalists and officials at the Colorado Public Employees' Retirement Association

who feared being cut out of lucrative investments.

Similar bills have passed in Virginia and are pending in Massachusetts and Illinois as public pension and endowment funds attempt to balance open-records laws with confidentiality clauses in agreements they must sign to invest in venture-capital funds. This was the subject of a front-page article in The Wall Street Journal on May 11.

"Many of these state statutes are out of date and don't provide appropriate protection for truly confidential business information," including the business plans of start-ups in portfolios, says Carl E. Metzger, a Boston lawyer for venture capitalists and a specialist on open-records laws. "The information about the portfolio companies can [include] trade secret technology, business strategies and a company's competitive position that would be the death knell for some of these companies if it were publicly released to its competitors. What's at risk here is the crown jewels of some of these companies."

The Michigan Press Association fought the bill introduced in the legislature there, which was more sweeping than what eventually passed. "When we started negotiating, there was going to be no information given out," says Dawn Phillips Hertz, the journalist group's lawyer.

As passed, the law shields confidential portfolio and investment information, and will make it more difficult to pry out individual return data by firm. But it requires the university to release the names of all its venture firms' start-up companies, the aggregate sums invested in them and the rate of returns on those investments annually. "The downside is the public has given up the right to see that information quarterly," Ms. Hertz says. "A lot of money can go down the drain in a year."

Some states are bucking the trend. The University of Texas Investment Management Co., for instance, won't invest in venture firms that refuse to disclose certain data, including rates of return.

The National Venture Capital Association says it hasn't taken a formal position on such bills, and some in the industry say their colleagues' fear of open-record requests -- commonly called FOIAs, after the federal Freedom of Information Act -- is overblown.

Gerry Langeler, a partner at OVP Venture Partners in Seattle, made that argument in an online piece this month. Its headline: "FOIA? GOIA! (Translation: Freedom of Information Act? Get Over it Already!)" He argues that venture capital funds and other private equity firms long have accepted public money without being hurt by disclosure. Moreover, funds can simply refuse to release to any clients -- public and private -- information they don't want made public, he adds, noting that some firms have started doing that.

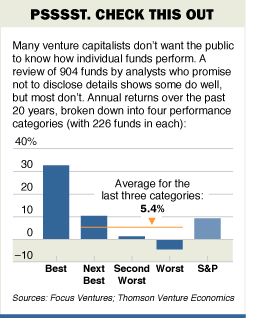

He says what is really at issue is big-name venture firms' fears that their images will be tarnished if everybody knows that some of their funds don't do very well and that the public might be frightened by the volatile, risky nature of venture investing. Mr. Langeler says one of his firm's biggest and oldest limited partners, the Oregon Public Employees Retirement Fund, has published return data for years, with little negative impact. "Our numbers are our numbers. When we do well, we're delighted to have them visible. If not, we're responsible for them nonetheless. In any event, we can't hide from them," he wrote in his online article.

In Colorado, state Treasurer Mike Coffman, a member of the state's employee pension board, opposed the recently enacted law there because the pension fund, which has seen its investments plummet in recent years, has "not been forthcoming in addressing their financial problems and not communicating them," says Brian Anderson, Mr. Coffman's spokesman. "Disclosure should trump confidentiality."

The pension fund's spokeswoman, Katie Kaufmanis, argues that the law was needed to protect companies financed by the venture funds, but will allow disclosure of how well each fund did. "Those are private companies and that is proprietary information should not be public because that could harm the value of our investment," she said.

Alan Salzman, managing director at VantagePoint Venture Partners, in San Bruno, Calif., said the limits on open-records laws are needed to stop "third parties who wish to resell the data" they can plumb from public-institution files. "VCs don't want to live in secrecy," he says, but they are duty-bound to keep their start-up companies' secrets. "We can't disclose that information without their consent and they are not consenting to disclose this information to their competitors. We don't have a choice," he adds.

Write to Ann Grimes at ann.grimes@wsj.com