|

|||

|

|||

The tax benefits of debt are a big deal and explain why companies are so eager to borrow money to fund operations. However, debt comes with costs. The most critical of these is bankruptcy and while the direct or deadweights costs of actually going bankrupt (and ending up in the legal system) are a component, an even more critical component is indirect bankruptcy cost. That is the cost that arises because people perceive that a company is in trouble, because of its debt, and change the way they interact with it. In particular, customers stop buying its products, suppliers demand cash and employees abandon ship. In this puzzle, I focus on the fall from grace of Valeant, a company that was viewed as a star performer in the pharmaceutial sector just about a year ago, with a market capitalization exceeding $100 billion, but has since seen its reputation destroyed, its top management team discredited and in serious jeopardy from its debt overhang.

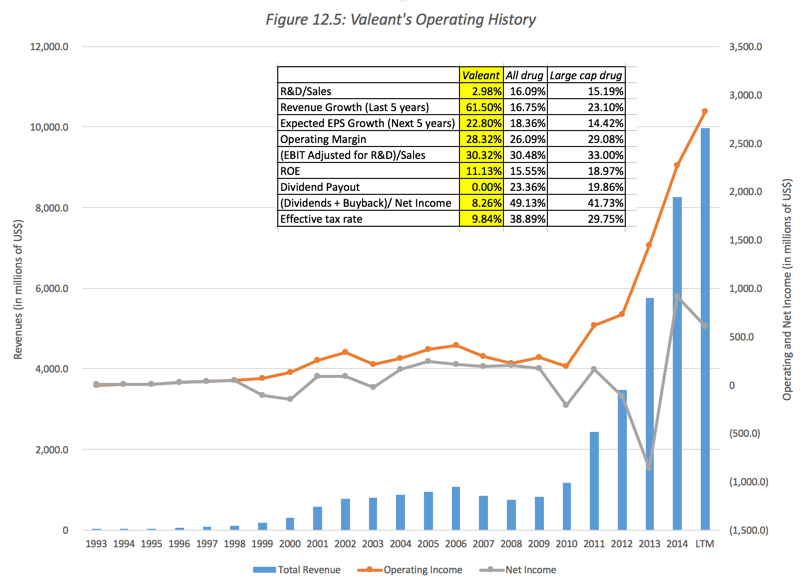

To get an overview of Valeant's rise from an obscure Canadian company to value investing darling, take a look at this graph that shows revenues, operating and net income for the company by year:

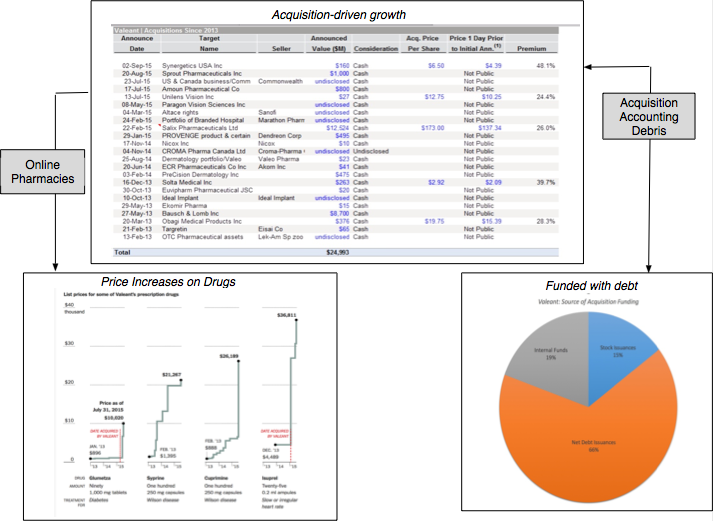

The surprising aspect of this growth was this happened in a sector (pharmaceuticals) where growth was not only slowing but becoming less value creating. In fact, note how much faster Valeant is growing than the rest of the sector, while also delivering higher operating profit margins than other drug companies. To the question of how Valeant pulled off its outlier status, the answer lies in their business model built on a combination of three variables: a growth strategy built around acquisitoins (rather than R&D), using a lot of debt in making those acquisitons and repricing existing drugs to deliver higher profits.

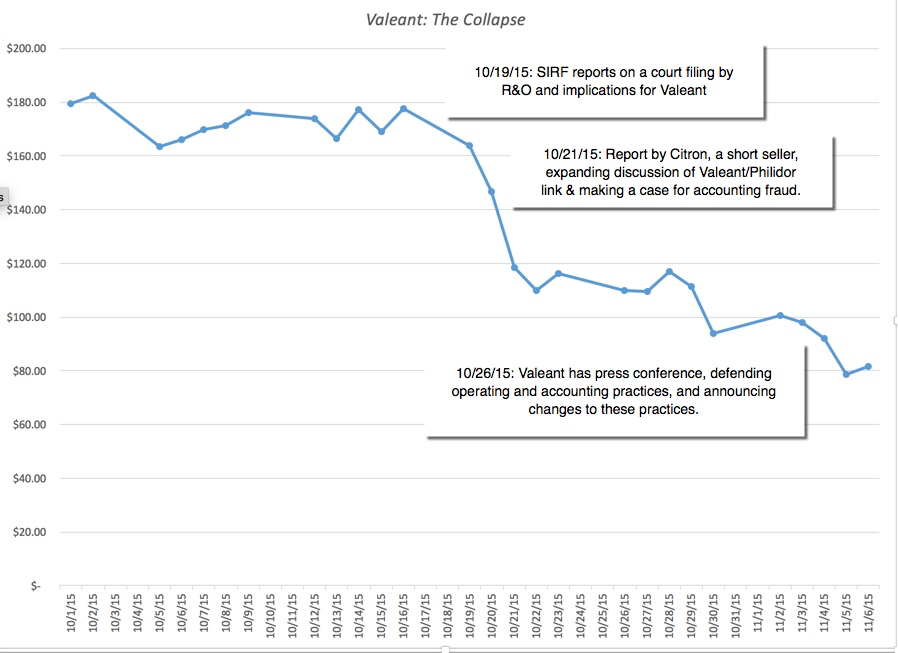

This model, while economically defensible, is one that is best delivered under the radar and Valeant was unable to stay unnoticed for two reasons. The first is that it became too successful, and its rising market cap, in contrast to other pharmaceutical companies made it the center of attention, often admirising from investors and other drug companies. The second is that its last acquisitoin in 2015 of Salix was its largest and the Salix drugs that it repriced in the aftermath were too big to go unnoticed. In the summer of 2015, Valeant was already the focus of legislators who were concerned about drug price increases. That focus became more intense after a short seller, in September 2015, pointed to Philidor, an online pharmacy that Valeant used, as a key (and perhaps illegal) component of the price increase strategy. Valeant's initial response, a mixture of bluster, defensiveness and hyperbole did not help and the stock price dropped to $80 by early November 2015:

In November 2016, I argued that Valeant's business model was broken and even if thier prevaling problems passed, they would be unable to go back to their old business model. I valued Valeant at about $72, on the assumption that they would now have to now behave like other large pharmaceutical companies and try to grow with R&D and internal investments. You can see my views in this post.

Valeant's Debt Problems

In the period since that post, things have gone from bad to worse at Valeant, with much of the damage self-inflicted. First, the management continued to argue that Valeant's growth historically had come from R&D and volume increases, when the facts on the ground clearly contradicted them. Second, Mike Pearson, the CEO of Valeant and ex-McKinsely consulant, who was a prime architect of its acquisition/debt/price incrase strategy stepped down for medical reasons just before Christmas, leaving the company rudderless for a while. Third, the Philidor mess got bigger and potentially more dangerous as Valeant was forced to retract earlier statements and announce a break with Philidor could have consequences for revenues and profits. Fourth, the company had to delay its financial filings, due in February, as it tried to get a handle on its own numbers. The market, not surprisingly, reflected these problems, with the stock price dropping below $30 in late March.

Valeant's failure to file its financials also had another negative side effect, insofar as it raised the possibility that company might not be able to file its financials by April 29, triggering covenants in its debt that coud result in legal consequences. AIn the meantime, without a management team in place, legal challenges and crisis paralysis, there was a concern that revenues and earnings, once restated, would be much lower than expected and that was spooking creditors. Valeant's bond rating, not surprisingly, is under siege and Valeant may very well fall into junk bond status. Valeant's debt troubles also created talk that Valeant may have to see some of its crown jewels to get cash to pay down debt. Even in this mission, Valeant's ill repute seemed to be getting in the way of selling assets, as potential buyers either underbid or walked away from the bidding table. To top it off, Valeant's biggest investor and booster, Bill Ackman announced that he was selling his shares in the company. Having bought the stock at $32 and having doubled my holding when the stock dropped to $14, I revisited the company in a recent blog post and wondered whether the damage created by the company during its debt-driven, acquisition-based high growth days was so lasting that it could never recover:

http://aswathdamodaran.blogspot.com/2017/03/a-valeant-update-damaged-goods-or.html

So, is the stock cheap at $11/share? I am continuing to hold but my faith is sorely tested.

Key Questions