In 2005, Companies Set a Record for Sharing With Shareholders

By FLOYD NORRIS

AMERICAN companies have plenty of cash, and they are sharing it with their

owners.

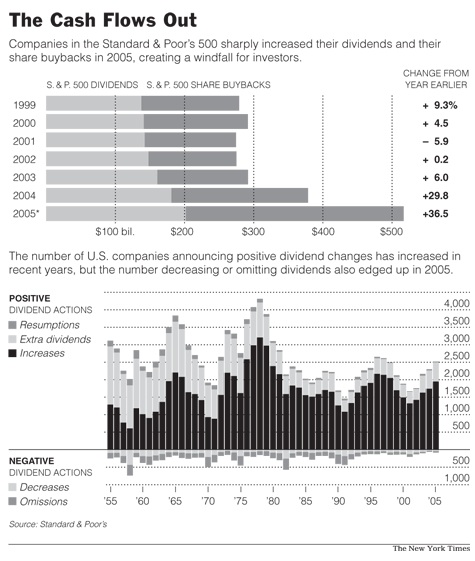

Companies in the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index paid a record $202

billion in dividends last year, up 11 percent from 2004.

But the real action was in share buybacks. Those 500 companies spent an estimated

$315 billion on buybacks, up 60 percent from the $197 billion they spent in

2004, an amount that was also a record.

That means that cash distributed by those companies to shareholders, past

and present, rose 37 percent during the year.

It might have been even better than that. While dividend payments are easily

measured, stock buyback figures are not disclosed until financial statements

are filed. Companies bought back more than $80 billion in shares in each of

the first three quarters, but Howard Silverblatt, the S.& P. analyst who

provided the figures, estimated only $70 billion for the final three months.

It might have been even better than that. While dividend payments are easily

measured, stock buyback figures are not disclosed until financial statements

are filed. Companies bought back more than $80 billion in shares in each of

the first three quarters, but Howard Silverblatt, the S.& P. analyst who

provided the figures, estimated only $70 billion for the final three months.

All that money has helped to buoy the stock market, no doubt, but some of

it may have also helped to support consumption by Americans.

For years, many on Wall Street argued that share buybacks were a better way

than dividends of returning cash to shareholders, but the big surge in such

buybacks came only after one major advantage of buybacks - in the tax code

- was removed. Now the United States taxes both dividends and capital gains

at a 15 percent rate.

One advantage of buybacks for companies is that they can be reduced when cash

is not available much more easily than dividends can be cut, given that dividend

reductions are seen as a sign of distress. But cash from buybacks goes only

to shareholders who sell, which seems to penalize loyal shareholders.

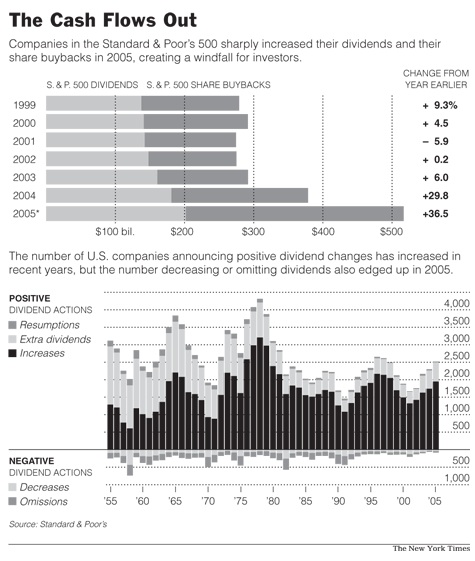

With help from good cash flow and encouragement from the tax law - which may

yet expire in 2008 if Congress does not act - 1,949 announcements of dividend

increases were counted last year by S.& P., up 12 percent from 2004 and

the most since 1998.

Not all companies are doing well, of course, and there were 84 negative announcements

- of either dividend reductions or eliminations - in 2005. That was up 31 percent

from 2004, but it was also the second-lowest total on record, going back to

1955.

Dividend levels were once deemed to be an important indicator of value in

the stock market, but that faded in the 1990's as companies that paid no dividends

became popular with investors who assumed they would be amply rewarded with

capital gains.

The actual level of dividends in the S.& P. 500 last year amounted to

just 1.8 percent of the year-end market value of the index, a figure that was

well above the 1.1 percent recorded in 1999 but still paltry by historical

standards.

But if one views buybacks as a form of dividend, then the combined payouts

for both 2004 and 2005 produced yields on year-end values of 4.6 percent -

figures that in the old days would have been seen as an indication that stocks

were a good buy.

Or perhaps all those buybacks are simply an indication that corporate America

has good profits now, but a dearth of attractive investment opportunities for

all that cash. If so, the big rise in buybacks is not so encouraging to shareowners.

It might have been even better than that. While dividend payments are easily

measured, stock buyback figures are not disclosed until financial statements

are filed. Companies bought back more than $80 billion in shares in each of

the first three quarters, but Howard Silverblatt, the S.& P. analyst who

provided the figures, estimated only $70 billion for the final three months.

It might have been even better than that. While dividend payments are easily

measured, stock buyback figures are not disclosed until financial statements

are filed. Companies bought back more than $80 billion in shares in each of

the first three quarters, but Howard Silverblatt, the S.& P. analyst who

provided the figures, estimated only $70 billion for the final three months.