Yet over all, emerging markets seem perched on solid ground. "We don't

see the traditional emerging-market risk factors," Jeffrey D. Sachs, the

Columbia University economist, said. "We are not moving off of a preceding

period of euphoria."

Yet over all, emerging markets seem perched on solid ground. "We don't

see the traditional emerging-market risk factors," Jeffrey D. Sachs, the

Columbia University economist, said. "We are not moving off of a preceding

period of euphoria."Developing countries seem more solid financially than they have in years. The prices for their raw material exports are strong. Their economic growth is picking up broadly. Global interest rates are low, but most of the current accounts of these nations are in surplus, so they do not need to borrow much money from the rest of the world, anyway.

Yet it took only a few words from the Federal Reserve a couple of weeks ago - replacing its promise of low rates "for a considerable period" with a promise to be "patient" before raising them - to send developing country debt into a financial swoon. The frisson provided an abrupt reminder of the effect that tighter credit in the United States would have on the economies of the developing world.

"It was a warning shot of what's to come when interest rates go up," said William Rhodes, a senior vice chairman of Citigroup.

In the two days after the Fed's statement on Jan. 28, the price of insurance against a default on Brazil's foreign bonds jumped 25 percent, to a little under 5 cents on the dollar. The price to cover against a default by Turkey spiked by more than 20 percent, to just under 4 cents. Some developing country stock markets were pummeled, and the prices of their bonds fell.

According to Mr. Rhodes, who has been dealing with emerging market debt crises since Jamaica's in the 1970's, "the situation is in a way reminiscent of the very early months of 1997, before the Asian financial crisis."

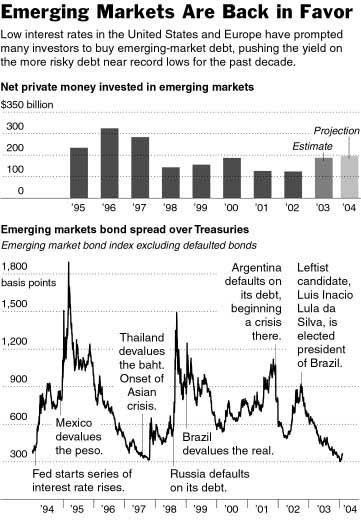

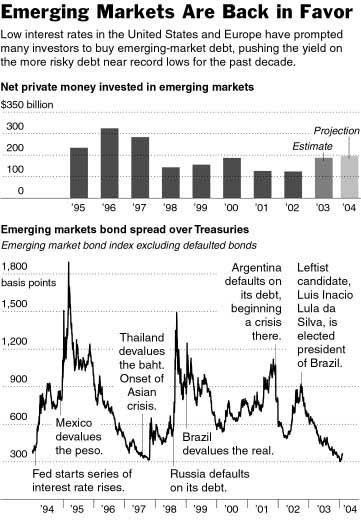

What worries Mr. Rhodes is that investors have been pumping money into developing countries with an intensity not seen since the mid-1990's, when capital flowed to "emerging markets" like water flowing downhill. According to the Institute of International Finance, a lobbying group for big banks, private capital flows to the developing world topped $187 billion in 2003 - the biggest total since 1997 - and will probably exceed $196 billion this year.javascript:pop_me_up2('/imagepages/2004/02/16/business/17PLACE.chart2.jpg.html','361520','width=431,height=670,scrollbars=yes,toolbars=no,resizable=yes');

With interest rates in the industrial world at 40-year lows, investors have sought higher returns ever further afield. They have aggressively snapped up developing country debt, bidding up bond prices with little heed, often, to the creditworthiness of the issuer.

In the process, the spreads on emerging market bonds - the premium they pay over the yield of United States Treasury bonds to compensate for their riskiness - have dropped to seven-year lows.

Unfortunately for the beneficiaries of this largesse, investors can be fickle. In the mid-1990's, money was also pouring into many developing economies. Then, in the summer of 1997, Thailand devalued the baht. The flood of money virtually stopped, emerging market spreads soared and a string of economies from Thailand to Indonesia to Russia to Brazil bit the dust.

Could the same thing happen today, if, say, the anticipated rise in United States interest rates prompted American investors to bring their money back home?

"In my opinion it is going to be milder than in 1997. But the direction is clearer than the intensity," Paulo Leme, director for emerging markets' economic research at Goldman, Sachs, said. "If there is a tightening of monetary policy in the G-7 countries, there could be temporary dislocations that either reduce, increase the price, or outright interrupt the capital flows to some of these countries."

The power of the blow will depend on three things, analysts say: how abruptly interest rates rise in the industrial world, how the rise affects investors' appetite for emerging market investments, and how well the emerging markets are prepared to withstand investors' loss of appetite.

The good news is that most developing economies are strong. "The outlook for emerging markets is the most positive we have seen for years," said Kristin J. Forbes, a member of President Bush's Council of Economic Advisers. "For the first time since 2000, every country in Latin America will grow."

Emerging markets, she added, are expected this year to repay more to the International Monetary Fund, the World Bank and other international financial institutions than they borrow, for the first time since at least 1978.

Unlike 1997, when emerging markets needed foreign money to cover current account deficits amounting to some $70 billion, last year every developing region - Asia, Latin America, Central and Eastern Europe, and Africa and the Middle East - recorded a current account surplus. Most foreign money flowing to developing countries is direct investment in factories and equipment, rather than volatile portfolio capital.

And developing countries have learned from the scorching crises of the late 1990's. They have kept a lid on short-term debt and have tucked away cushions of foreign reserves to soften the blow of any eventual drop in foreign financing. Most of them have floated their currencies, to avoid having to spend reserves defending fixed exchange-rate regimes.

There are weak links, of course. In a report issued in January, the Institute of International Finance suggested that the relatively poor economic outlook of countries like Ecuador, Venezuela, Peru, Egypt and the Philippines did not justify the level of capital flows into those countries, implying that the financing could snap back.

The institute warned that developing countries must stay the path of orthodox economic management, meaning tight fiscal policies and market-friendly economic reforms, to ensure that capital flows continue.

Yet over all, emerging markets seem perched on solid ground. "We don't

see the traditional emerging-market risk factors," Jeffrey D. Sachs, the

Columbia University economist, said. "We are not moving off of a preceding

period of euphoria."

Yet over all, emerging markets seem perched on solid ground. "We don't

see the traditional emerging-market risk factors," Jeffrey D. Sachs, the

Columbia University economist, said. "We are not moving off of a preceding

period of euphoria."

Since January 2003, Moody's Investors Service and Standard & Poor's between them have upgraded the credit outlook for 25 developing countries and downgraded only 5.

Stable emerging markets are not guaranteed to avoid crises, however. If properly motivated, investors can provide the requisite instability. And lately, potentially unstable money has become a bigger part of the flow.

According to the Bank for International Settlements in Basel, Switzerland, the entity that sets global banking standards, in 1998 about 30 percent of the trade in developing country debt was accounted for by leveraged hedge funds - fickle investors that tend to pull money wholesale out of one market to cover margin calls on losing investments elsewhere.

By 2002, this percentage dropped to only 10 percent, while activity by high-quality investors - like pension funds - grew to represent 28 percent of the market.

Yet as emerging market debt prices surged last year, leveraged investors were drawn back in. Data compiled by Jonathan Bayliss, global head for quantitative strategy at J. P. Morgan Chase's emerging markets' research group, indicate that by the end of 2003, the hedge funds were responsible for roughly 17 percent of the trading volume in emerging market debt, while business by more patient investors dropped to 21 percent of the total.

Yet while leveraged investors might magnify the effect on emerging markets of financial fluctuations in the United States, ultimately the magnitude of any rise in interest rates here will determine the power of the shock.

If, as many investors expect, the Fed increases rates only moderately and does not bring growth in the United States to a halt - and if the large federal budget deficit and the decline in the dollar do not spur a spike in market interest rates - then emerging markets could sail through unscathed.

Emerging market bonds would decline, so developing countries would find it more expensive to borrow money. But that cost would be counterbalanced by firm commodity prices and a strong American economy sucking in developing country exports.

"If rates go up in this country because of global reflation, emerging markets gain more than they lose," said Mohamed El-Erian, head of emerging markets portfolio management at Pimco, the mutual fund company.

The Fed-induced financial tremors two weeks ago could even prove beneficial for the developing world, shaking out some of the frothy short-term hedge fund money and leaving long-term, strategic investors in place.

But it would be unwise to bet too heavily on such smooth sailing. "If interest rates go up because people lose faith in the dollar, or hesitate to fund the ever growing U.S. budget deficit, that would be unambiguously negative for emerging markets," Mr. El-Erian said. "We think the first scenario is much more probable, but we have to monitor both."