Your life insurance is meant as a hedge against personal tragedy. Wall Street increasingly wants to invest in it like a security.

Some of the world's largest insurers and investment banks are selling bonds linked to life insurance and the immense cash flows associated with it. They are hoping to do something similar to what home lenders did in recent decades, when they packaged mortgages into securities that could be purchased by third parties and traded in a huge secondary market.

These bonds can take a number of forms. Some, which go by the name "XXX" bonds, are backed by the piles of capital that insurers hold against typical policies. Others are pegged to death rates, and investors could lose out in a catastrophic event, such as an outbreak of bird flu.

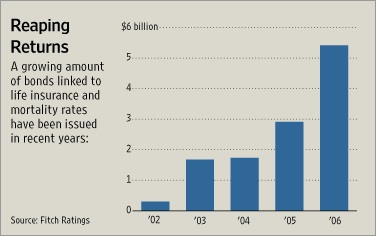

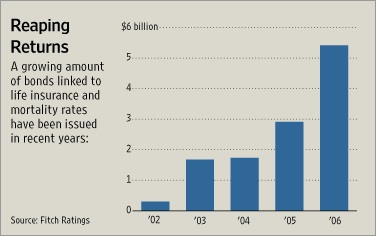

Last year, insurers sold $5.4 billion in bonds linked to life insurance and

mortality, according to Fitch Ratings. That is a tiny sum compared with the

multitrillion-dollar market in mortgage-backed securities, but insurers had

issued $6.7 billion in the prior four years combined. Buyers typically were

hedge funds, pension funds and other institutional investors, rather than individuals.

In January alone, insurers issued another $880 million. Major companies such as Swiss Reinsurance Co. and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. are wading deeper into the business.

Those figures don't include another small strain of investment -- also the most controversial -- that is an offshoot of 1990s viaticals, in which investors buy into life insurance policies and are paid when individuals die.

"There's a huge appetite for insurance risk in the marketplace," says Joseph Zubretsky, an executive at UnumProvident Corp., a disability insurer, which is involved in bonds associated with disability policies, part of the broader life-insurance industry.

Investors are showing interest in part because they are so hungry to diversify their bets, a lesson many learned when the Internet-stock bubble burst a few years ago.

Back then, money managers who held unconventional assets -- timber, for example -- fared much better when share prices tanked. Those unconventional assets were largely untouched by the plunge. Ever since, investors have been hunting for new ways to make money even if stocks or corporate bonds turn down.

Insurance could fit the bill. The number of people who die prematurely or suffer disabling injuries has little connection to stock or typical bond prices.

"Investors are gradually becoming aware that these are truly uncorrelated risks," says Rob Procter, co-head of Securis Investment Partners, a London hedge fund that invests solely in insurance-linked securities.

A transaction involving UnumProvident shows how some of these deals can work. Because of regulatory requirements, the Tennessee company had to set aside $1.5 billion in capital to back policies for thousands of sick or injured clients. If health-care costs unexpectedly spiked or disability claims started rising, the company would draw from the pool to pay claims.

UnumProvident figured the price of care was predictable, and the chances of needing the extra money were slim. So it issued bonds against it. The bonds will be paid back over time with interest if the money isn't needed to pay off claims. The insurer, meantime, took in $130 million upfront.

By freeing up cash they would otherwise need to hold aside for future claims, insurers can invest for higher returns, give the money back to shareholders or use it to write more policies.

Meantime, if claims spike, the investors could be out of luck. The insurer can tap into the cash pool created by the bonds to pay policyholders. Either way, policyholders are paid by the insurer, as regulators demand.

"It is a powerful, broad tool," says Cheryl Whaley, who heads the capital markets unit at Genworth Financial Inc., of Richmond, Va., which has done four similar deals.

Bonds linked directly to an insurer's reserves are known as "XXX," a name that comes from a regulation that officials use in setting reserve requirements.

Another type of transaction involves "mortality catastrophe bonds," in which bond buyers contribute to pots of money that insurers can tap into if large numbers of people die in a disaster.

The bonds help insurers limit their exposure. If disaster doesn't strike, the investors get their money back with a preset return, typically a premium above some benchmark interest rate.

Swiss Re has issued five bonds linked to life insurance and mortality already, the latest of which raised more than $700 million from institutional investors.

French insurer AXA SA has also issued similar bonds, as has Aegon NV, a Dutch insurer which did two deals last month, including one that freed up about $175 million for the company.

The bonds represent less than 1% of Aegon's overall liabilities, which shows how small the market is now, but also how much more it could grow if investors and insurers fully embrace it.

"These are tryout deals," says Joseph Streppel, Aegon's chief financial officer.

While it is expanding fast, several factors could limit the size of the market. Mortgage loans are highly standardized, making it relatively safe and simple for investors to invest in them. Life-insurance policies, on the other hand, can vary greatly from company to company, making bonds tied to them harder to evaluate as an investment.

Moreover, a mortgage loan is backed up by the physical asset of a house. There is no equivalent in a life insurance policy. The returns depend on external circumstances, such as how many people die in a given year.

The deals have the potential to alter how the public views insurers. No one knows how consumers will react if insurers that portray themselves as financial life partners routinely act as middlemen between policyholders and bond buyers.

"Does that relationship suffer?" says Nicholas Potter, an attorney with Debevoise & Plimpton LLP who has worked on several deals. "It's a question mark."

Still, investors are getting accustomed to the deals. Many of the bonds are insured, which means the returns were guaranteed. Some are willing to drop that insurance in exchange for a chance at a higher return, according to Mr. Potter.

Proponents predict the market could expand significantly in coming years. "We have a very active year planned," says Michael Millette, head of financial-institutions structured finance at Goldman Sachs in New York.

Swiss Re says the market for all insurance-linked securities, a field that also includes catastrophe bonds tied to coverage for damage from natural disasters, could be more than ten times greater by 2016.

"Does $350 billion make sense? It could," says Dan Ozizmir, a managing director at Swiss Re who oversees the company's insurance-linked securities business. "The raw material is there."

Write to Liam Pleven at liam.pleven@wsj.com and Ian McDonald at ian.mcdonald@wsj.com