Dividends, Buybacks Set New Benchmark for Largess As Corporate Coffers Swell,

Holders Reap the Rewards;

The $1,700-a-Head Bracket

By IAN MCDONALD

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

November 28, 2005; Page A1

Cash-rich American companies are showering a record windfall on their shareholders

-- and in the process stirring some concern about future growth of the U.S.

economy.

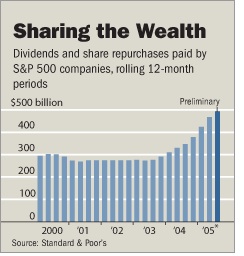

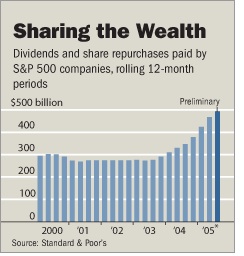

This year, the companies in the Standard & Poor's 500-stock index are

on track to pay out more than $500 billion to shareholders in the form of dividends

and share repurchases, or buybacks, according to S&P. That's up more than

30% from last year's record -- and equivalent to nearly $1,700 for every person

in the U.S.

"This is an enormous amount of money being paid, to some degree, in unison," says

Howard Silverblatt, an equity-market analyst at S&P in New York.

The outpouring of cash from corporate coffers in the U.S. is just one aspect

of a world-wide phenomenon. With interest rates low, unprecedented amounts

of capital are sloshing around the globe, in search of better returns. Pension

funds, mutual funds and insurance-company accounts, for example, have some

$46 trillion in assets, up almost a third from five years ago.

The flood of dividends and share buybacks is a direct result of record U.S.

corporate profits and is welcome news for shareholders, particularly because

dividends are taxed at lower rates and share prices have been flat; since the

beginning of the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen a paltry

1.4%.

The flood of dividends and share buybacks is a direct result of record U.S.

corporate profits and is welcome news for shareholders, particularly because

dividends are taxed at lower rates and share prices have been flat; since the

beginning of the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen a paltry

1.4%.

Just this month, 23 companies in the S&P 500 have boosted their dividends,

including General Electric Co. and toy maker Mattel Inc., which also expanded

their share-repurchase plans. For the year as a whole, 275 companies in the

S&P 500 have raised their dividends; only eight have cut them.

In some cases, institutional investors, including mutual funds and activist

hedge funds, are the driving force behind the bigger dividends and buybacks.

This year, for example, New York financier Carl Icahn lobbied for a higher

dividend at Blockbuster Inc. and a more aggressive stock buyback program at

Time Warner Inc., companies in which his Icahn & Co. hedge fund owns big

stakes.

The sharp rise in dividends and buybacks could have major ramifications for

investors, corporations and the economy as a whole, depending on where the

torrent of cash ends up. The payouts could provide a new boost for consumer

spending or could push up stock prices if shareholders reinvest dividends in

stock.

But there could be an economic downside to the cash glut. The fact that companies

have been sitting on so much cash is, in some respects, a vote of no-confidence

in U.S. economic prospects: At least some companies may be signaling they can't

find enough profitable ways to reinvest their earnings, so they are simply

returning it to shareholders.

Through dividends, a company, in effect, distributes part of its profits directly

to shareholders. Share buybacks, in which a company buys some of its own shares

outstanding, can benefit shareholders in other ways: They can boost the company's

share price, and they can also be a smart corporate investment if the company

correctly judges that its stock is undervalued.

The recent and sharp rise in these payouts marks a significant transformation

in the way companies allocate their profits -- sharing more with investors,

instead of reinvesting their businesses. If the trend persists, it would mark

a return to historic norms in which dividends made up a big part of an investor's

return.

The recent and sharp rise in these payouts marks a significant transformation

in the way companies allocate their profits -- sharing more with investors,

instead of reinvesting their businesses. If the trend persists, it would mark

a return to historic norms in which dividends made up a big part of an investor's

return.

Dividends have been on the rise since the Bush administration succeeded in

cutting the tax rate on them to 15% in 2003, as opposed to taxing dividends

as regular income. But that tax cut is set to expire after 2008 and extensions

have stalled thus far in Congress amid steep budget and trade deficits.

Even after the recent rebound in dividend payments, however, the average S&P

500 stock has a dividend yield of just 1.8% -- about half the historical average.

Currently, U.S. companies are sitting on near-record levels of cash. Among

industrial companies in the S&P 500, a grouping that excludes financial

firms, which are required to hold hefty reserves, the amount totals nearly

$631 billion on the books. That figure represents more than 7% of these companies'

market value -- the highest percentage since 1988.

Some economists call the payouts this year an ominous development that may

be stealing from future economic growth, since they suggest companies are having

trouble spotting new products, projects or services they think will boost their

growth. "These payments keep the economy growing more slowly because that

money isn't flowing into capital spending," says Milton Ezrati, chief

economist at Lord Abbett Funds in Jersey City, N.J. "If businesses are

giving up on innovation, we have problems."

Others could argue, however, that U.S. companies are merely starting to bring

their payouts to shareholders back near historical levels in a mature economy

with more pressure for shareholder-friendly corporate governance in the wake

of accounting scandals.

A big driver of the record profits making these payouts possible isn't a runaway

economic boom, but rather deep corporate cost-cutting in recent years. After

the accounting scandals and economic downturn that followed the end of the

tech bubble, executives pulled in their horns. Instead of shopping for acquisitions,

many companies have refinanced debt to take advantage of lower interest rates

and hacked away at costs that built up during frothier times.

While acquisition activity has ticked up in recent quarters, deep-pocketed

private-equity firms have made many of these purchases, rather than companies

spending from their war chests. As a result, mammoth mergers haven't been as

common as in the heady 1990s.

"Over the past five or so years we've had a bear market, corporate scandals

and a lot of geopolitical uncertainty, so a lot of executives hunkered down," says

Michael Maubossin, chief investment strategist with Legg Mason Capital Management.

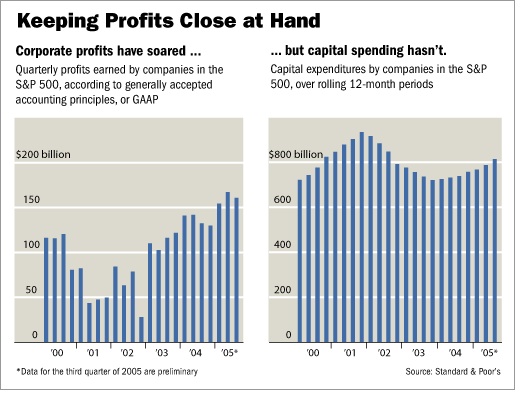

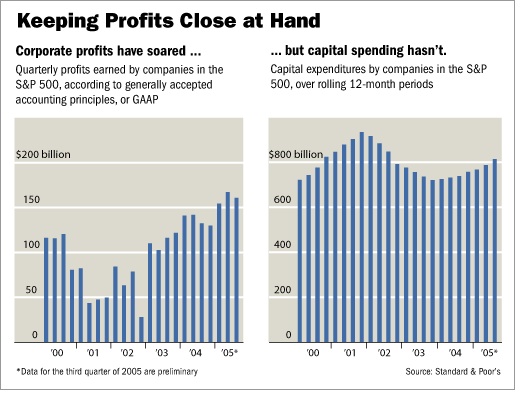

Indeed, capital spending by the companies in the S&P 500 has grown only

modestly over the past two years, after two years of declines, according to

S&P.

So when the economy finally got some traction in recent years, companies were

leaner and more profitable. For a record 14 consecutive quarters, companies

in the S&P 500 have reported double-digit profit growth, according to S&P's

Mr. Silverblatt. His firm's projections have the record streak lasting at least

two more quarters.

If profits do remain strong, however, employees and unions may put pressure

on companies to direct more of that money to higher wages and benefits, after

several quarters of modest wage growth and benefit cuts at many firms amid

rising health-care costs.

So far, companies have felt free to spend a big chunk of their profits on

their own stock. This year, nearly 60 companies in the S&P 500 have cut

their number of shares outstanding by at least 4% through repurchases, according

to S&P.

Overall, in the first nine months of this year, S&P 500 companies paid

out $147 billion in dividends and spent $231 billion on share repurchases --

a figure that includes only actual purchases, excluding buybacks not yet completed.

Mr. Silverblatt of S&P expects dividend payouts and share repurchases for

S&P 500 companies to top $500 billion for the full year.

To put that figure in perspective, it could pay off the federal budget deficit

for the just-ended fiscal year with about $180 billion to spare.

And many companies have plenty of money left over after increasing their dividends

and buyback programs. Even after paying out $10 billion in dividends next year

and spending $3 billion on capital expenditures, for instance, GE expects to

have an extra $11 billion in free cash after paying its overhead next year.

"We've tried to accommodate investors who want a dividend, those who

want buybacks and also those who want us to keep growing the company," says

Keith Sherin, GE's chief financial officer.

Although dividends and buybacks are often lumped together, they have considerably

different implications for a company and its investors. A quarterly dividend

check can serve not only as a carrot for investors, but also a check on overspending

for corporate managers. Research has shown that companies that pay dividends

tend to have healthier long-term profits than those that don't.

A share repurchase can be a plus for investors too: If a company buys its

own shares when they are cheap, it can support the stock price and thus boost

investors' returns. Of course, the opposite holds true if the company buys

at a price well above the shares' value.

Share repurchases have many fans on Wall Street, particularly with shares

of big "growth" companies trading at their lowest valuations in years.

For years they had the upper hand over dividends because they were viewed as

more tax efficient. That argument has been sapped a bit by the dividend-tax

cut.

Dividend checks are favored by many investors. A dividend is cash in hand,

after all, whereas the value of a share repurchase depends on whether the company

is buying shares at an attractive price.

"A dividend is better than a buyback for investors," says Patrick

Dorsey, head of stock analysis at Chicago researcher Morningstar Inc. "The

company is saying we're going to give you some of our income each quarter,

and as a result we're going to have to think harder and smarter about what

we do with the rest of that money."

The good news for dividend fans is that it looks like there's ample room for

these checks to grow from here. Today, 385 companies in the S&P 500 pay

dividends, down from a peak of 469 in 1980. And even though billions are going

out the door, dividends only comprise about 32% of payers' profits. Historically,

companies have paid out about 54% of their profits as dividends.

Write to Ian McDonald at ian.mcdonald@wsj.com

The flood of dividends and share buybacks is a direct result of record U.S.

corporate profits and is welcome news for shareholders, particularly because

dividends are taxed at lower rates and share prices have been flat; since the

beginning of the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen a paltry

1.4%.

The flood of dividends and share buybacks is a direct result of record U.S.

corporate profits and is welcome news for shareholders, particularly because

dividends are taxed at lower rates and share prices have been flat; since the

beginning of the year, the Dow Jones Industrial Average has risen a paltry

1.4%. The recent and sharp rise in these payouts marks a significant transformation

in the way companies allocate their profits -- sharing more with investors,

instead of reinvesting their businesses. If the trend persists, it would mark

a return to historic norms in which dividends made up a big part of an investor's

return.

The recent and sharp rise in these payouts marks a significant transformation

in the way companies allocate their profits -- sharing more with investors,

instead of reinvesting their businesses. If the trend persists, it would mark

a return to historic norms in which dividends made up a big part of an investor's

return.