How the Treasury Department Lost

A Battle Against a Dubious Security

By

JOHN D. MCKINNON and GREG HITT

Staff

Reporters of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

In 1993, Goldman Sachs & Co. invented a security that offered

Enron Corp. and other companies an irresistible combination.

It was designed in such a way that it could be called debt or

equity, as needed. For the tax man, it resembled a loan, so that interest

payments could be deducted from taxable income. For shareholders and rating

agencies, who look askance at overleveraged companies, it resembled equity.

To top officials at the Clinton Treasury Department, the so-called

Monthly Income Preferred Shares, or MIPS, looked like a charade -- a way for

companies to mask the size of their debt while cutting their federal tax bill.

Treasury made repeated attempts to curtail their use. In 1994, it

scolded Wall Street firms and asked the Securities and Exchange Commission to

intervene. The next year, the department sent legislative proposals to Congress

aimed at closing loopholes and punishing offenders. In 1998, the Internal

Revenue Service tried to disallow Enron's tax deductions. Each move was beaten

back by a coalition of investment banks, law firms and corporate borrowers, all

of whom had a financial stake in the double-edged accounting maneuver.

The MIPS saga shows how moneyed interests, with armies of

well-connected lobbyists and wads of campaign contributions to both parties,

defeated the Treasury's efforts to force straightforward corporate accounting.

With corporate bookkeeping now under scrutiny, the story of this flexible

financial instrument shows how such accounting gimmickry gained acceptance.

Enron's collapse cannot be traced to any one decision. But the

survival of MIPS was an early milestone for what became a series of

transactions in which the company borrowed more and more without making clear

that was what it was doing.

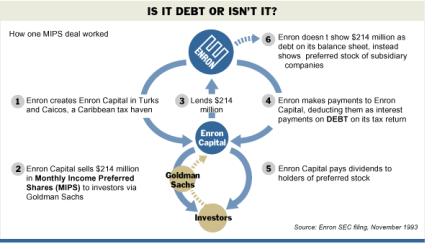

In the first of several similar deals, Enron in November 1993 set

up a subsidiary called Enron Capital LLC in Turks and Caicos, a Caribbean tax

haven. The unit sold about $214 million in preferred shares -- the MIPS -- to

investors through Goldman Sachs, promising an 8% annual dividend paid in

monthly installments. The subsidiary then lent the proceeds to the parent

corporation, to be paid back over 50 years or more.

Two

Treatments

Enron deducted from its taxable earnings about $24 million in

interest payments that it paid in 1993 and 1994 to Enron Capital, according to

IRS court filings. But in reports to shareholders, Enron described the

obligation as "preferred stock in subsidiary companies."

Even though Enron had in effect gone $200 million in debt, company

executives figured its credit rating would actually improve. Lea Fastow, then

working in corporate finance at Enron (and the wife of Andrew Fastow, later

Enron's chief financial officer) told Institutional Investor magazine in

October 1994 that the MIPS offerings were part of an effort to raise its rating

from triple-B to single-A by the end of 1995. By December 1995, Enron's credit

rating was up to triple-B-plus.

MIPS transactions would, she said, reduce the company's

debt-to-equity ratio. But Standard & Poor's, in its rating of November 1993

of the first MIPS deal, cautioned that Enron's financial maneuvers were

"aggressive and not particularly supportive of credit quality." A

spokesman for Ms. Fastow said she declined to comment.

From

Seedling to Forest

The details of MIPS were disclosed in SEC filings, which came to

the Treasury's attention almost immediately. Treasury officials feared this

seedling would sprout into a forest, and they were right. Enron, one of two

MIPS pioneers -- the other was Texaco -- eventually issued at least $1 billion

of MIPS and similar securities, known generically as "trust

preferred" securities. Texaco, now part of ChevronTexaco Corp.,

issued at least $525 million. Utilities, banks and other companies found them

attractive, too. In all, $180 billion of trust-preferred securities is

outstanding.

After reviewing the documents on Enron's 1993 transactions,

Treasury tax officials -- led by Leslie Samuels, then the assistant secretary

for tax policy -- moved quickly, hoping to act before too many other

corporations and individual investors become involved in MIPS-like deals. Early

in 1994, Treasury and IRS officials summoned investment bankers and lawyers to

express Washington's skepticism about the deals.

To put extra pressure on Wall Street, the Treasury officials

invited SEC staff to sit in on the meeting. The goal was to keep the investment

bankers from telling two different stories to the two sets of regulators:

telling the IRS that the problem was with how MIPS are handled in SEC filings,

and telling the SEC that it was a tax issue.

The Wall Street bankers and lawyers weren't persuaded. So the

Treasury beseeched SEC staff to stop the practice. "One of the pitches the

Treasury made was, 'Do you realize that companies have billions of dollars of

debt that isn't showing up as debt?' " according to an official who was

there. The SEC did little except recommend that companies change the way they

describe the securities. The SEC suggested describing them as

"company-obligated mandatorily redeemable security of subsidiary holding

solely parent debentures" or similar wording.

An SEC spokesman declined to elaborate on guidance the agency issued

that says companies should "consider the adequacy of disclosures"

about trust-preferred securities and "describe fully the terms" in

footnotes.

Later in 1994, the IRS issued a formal statement, warning

companies that it would be scrutinizing MIPS and similar securities, and would

consider rejecting interest deductions if they were for securities treated as

equity in corporate financial statements to shareholders.

All this had little effect, though. Merrill Lynch, with its

substantial base of retail investors, joined the party with a $75 million Enron

issue in 1994, dubbing its version Trust-Originated Preferred Securities. Other

companies did the same.

So in late 1995, looking for ways to raise tax payments by corporations

to reduce the federal budget deficit, the Treasury assembled a list of

corporate tax and accounting abuses to target, and put MIPS near the top of the

list.

Redrawing

the Line

In an unusual move, the Treasury unveiled its legislative proposals

on Dec. 7, 1995, criticizing "blurring of the traditional line between

debt and equity." The Treasury's tax proposals typically are a

little-noticed sidelight in the president's budget when it comes out in early

February.

"We knew Wall Street was working furiously to exploit tax

loopholes with financial instruments, and the industry correctly perceived that

we were targeting that activity," said Clarissa Potter, an ex-Treasury

official now at Georgetown University Law Center.

Businesses account for all sorts of transactions one way on their

tax returns and another way in shareholder accounts. Companies often depreciate

investments more rapidly on their tax returns -- which means bigger

depreciation charges that reduce profits subject to federal taxes -- than they

do in the profit reports they give shareholders.

But MIPS and their kin were particularly aggressive. And the

Treasury's proposals to quash them were tough. They would have denied the

interest deduction for any transaction lasting more than 20 years that was not

treated as debt for accounting purposes. They would have punished not only the

parent company but other businesses that got involved in the deals, denying

them another deduction that is available to corporations. The Treasury also

said its restrictions should be effective as of Dec. 7, no matter when Congress

acted. The Treasury estimated that its proposals would raise $800 million in

additional revenues over five years.

Wall Street reacted forcefully. "Dec. 7, 1995, is a day that

will live in infamy," Micah Green, head of the Bond Market Association, a

trade group, said publicly at the time, condemning the Clinton proposals.

The backers of MIPS and other trust-preferred securities assembled

a flotilla of well-connected lobbyists to fight the Treasury. Among them: Mark

Weinberger, who is now the Treasury's top tax official; Nick Calio, who was a

lobbyist for the first Bush White House and is now chief lobbyist in the

second; Fred Goldberg, who was the top tax official and IRS commissioner in the

first Bush administration; Kenneth Duberstein, who had been Ronald Reagan's

chief of staff; and Lawrence F. O'Brien III, who had been a lobbyist in the

Carter Treasury.

A law firm that did significant work for Enron, Vinson &

Elkins, registered as a lobbyist for both Enron and Goldman Sachs. Enron itself

reported lobbying expenses -- not counting campaign contributions -- of

$530,000 for 1996 and $1 million in 1997 on "budget and tax

legislation" including "corporate welfare."

Their first goal was to get rid of the Dec. 7, 1995, effective

date. Victory came in March 1996 when the chairmen of the tax-writing

committees, both Republicans, said that even if they adopted some Clinton

proposals, they wouldn't make them "retroactive."

But the Treasury continued to press its proposal to treat as

equity, and therefore ineligible for any interest tax deduction, any financial

instrument that had a term of more than 20 years and wasn't shown as debt on

the company's balance sheet.

The lobbyists successfully asked members of the House and Senate

tax-writing committees to announce their opposition to the Treasury proposals

in letters to colleagues or to the Clinton administration.

Those letters, in turn, became fodder for lobbyists seeking

broader support. The Bond Market Association would eventually assemble an

inch-thick collection of critical letters -- some from lawmakers and some to

them from financial-market critics of the proposals. "It's the heft of the

thing, the thud when it hits the table," says John Vogt, the bond

industry's top Washington lobbyist, who still keeps a copy.

One letter, signed by Jon Corzine, then chief executive officer of

Goldman Sachs, and 34 others portrays the Treasury as attempting to draw

"completely arbitrary" lines between debt and equity. Mr. Corzine,

now a Democratic senator from New Jersey, says it's unfair to equate Enron's

early use of the new financial instrument, which was disclosed in SEC filings,

with its subsequent creation of partnerships to hide debt and generate dubious

earnings.

'A

Legitimate Question'

"I'm not saying it wasn't aggressive tax policy -- that's why

the Clinton administration did what it did -- but it wasn't designed to hide

bad assets," Sen. Corzine says. "There was a legitimate question with

regard to the tax treatment," he said. But "lawyers said it was

right. Accountants said it was right -- not that that counts for much now --

and the courts said it was right."

As the battle intensified, the U.S. Chamber of Commerce and the

National Association of Manufacturers joined the fray. Merrill Lynch, in

written testimony to Congress, said there wasn't any need to worry because

trust-preferred securities "are issued by well-established companies that

are likely to remain in business throughout the term of the obligation."

Wall Street argued that everyone except the Clinton administration

was now comfortable with the securities and that the administration was simply

trying to raise business taxes. "The target may be Wall Street but the

victims live on Main Street. ... It is going to come out of people's pockets,

and the people who are paying are largely going to be workers and middle-class

savers," testified Mr. Goldberg, the former IRS commissioner then at the

law firm of Skadden Arps, which had helped structure some of Enron's

trust-preferred deals. Mr. Goldberg said at the time that he wasn't lobbying on

behalf of any specific client, though he acknowledged that several were

interested. He declines to comment now.

In the end, only a few Clinton corporate-tax proposals became law

in the summer of 1997. The proposals aimed at MIPS and other trust-preferred

securities were largely forgotten -- until Enron's collapse.

But the IRS didn't give up. In an audit of Enron's tax returns,

IRS field agents in Texas challenged Enron's deductions for its MIPS-related

debt. The argument was simple: the securities were more like equity than debt,

and dividends on equity aren't tax-deductible.

Enron appealed the IRS action to the U.S. Tax Court in April 1998.

The Wall Street lobbying forces swung into action again, unhappy that the IRS

action was making it difficult to do new trust-preferred securities. In the

summer of 1998, lawyers for the Wall Street Tax Association -- an organization

of tax professionals in the securities industry -- came to IRS headquarters in

Washington to complain that the challenge was legally flawed and unfair to the

now well-established markets in the securities.

"It would be a great pity if we all collectively are forced

to wait years for a Tax Court decision in Enron to establish what should be a

straightforward proposition," Ed Kleinbard, a lawyer who worked with the

association, wrote at the time in Tax Notes, a newsletter.

On Christmas Eve 1998, the IRS quietly folded, telling the Tax

Court that the deal was legitimate -- for tax purposes. "Enron Capital is

a valid entity that is separate and distinct from Enron for federal income tax

purposes," the IRS conceded. That meant that "the 1993 loan

constitutes indebtedness of Enron for federal income tax purposes."

Mr. Weinberger, the lobbyist-turned-Treasury official, says the

IRS decision to back away proves that the industry position was correct:

"We said this is a legitimate financing tool for corporations."

A spokeswoman for Goldman Sachs, Kathleen Baum, makes a similar

point: "Trust-preferred securities have become a standard component of

corporate finance issued by hundreds of companies across industries. There is

full disclosure in financial statements, and they are well understood by the

rating agencies." Defenders of trust-preferred securities say rating

agencies only give them some credit as equity. But critics say they should be

reported more clearly as debt.

Getting

Around the Rules

Lynn Turner, the SEC's chief accountant from 1998 to 2001, said

trust-preferred securities are an example of the aggressive accounting that

grew in frequency during the 1990s while regulators dawdled. "As a result,

we have balance sheets getting much better credit ratings than they should, and

companies looking more liquid and in much better financial shape than they are,"

he said. "This is a very good example of how the professional community,

including underwriters, attorneys and auditors, was trying to find ways to

structure things to get around the rules."

Since Enron's implosion, the Financial Accounting Standards Board,

which sets accounting standards, has revived efforts to resolve the controversy

over securities that purport to be debt for some purposes and equity for

others. The Treasury's deputy assistant secretary for tax policy, Pam Olson,

told a New York tax-lawyers group recently that there's new reason to think

about closing the gap between financial accounting and tax accounting. But

Treasury officials emphasize that they aren't among the agencies investigating

Enron's finances and haven't come to any conclusions about the role debt-equity

arrangements played in its collapse.

On Jan. 24, the senior Democrat on the House tax-writing

committee, Charles Rangel of New York, introduced legislation similar to the

Clinton Treasury's failed proposals. It would penalize companies unless they

disclose any debts as liabilities, even debts of off-balance-sheet

partnerships. "If Congressional Republicans had permitted action on that

[Clinton] proposal, we might not have seen the spectacular rise and collapse of

Enron," he says.

To which Mr. Vogt, the bond-market lobbyist, replies:

"Clinton dropped the proposals from his budget. Now that similar proposals

have resurfaced, we're on our way back to the Hill."

Write to John D. McKinnon at john.mckinnon@wsj.com and Greg

Hitt at greg.hitt@wsj.com

Updated February 4, 2002 12:01 a.m. EST