By PUI-WING TAM

January 31, 2007; Page C1

Venture capitalists are reaching into a new bag of tricks to cash out of their

investments.

For the past few years, it has been difficult for venture capitalists to cash

in on their investments in start-up companies. Historically, they drew out

their profits in the start-up businesses they financed by doing public stock

offerings, or outright sales of the companies.

It isn't so easy anymore. Despite a recent burst of activity, the pace of new

stock offerings remains muted, compared with the late 1990s and 2000. And acquisitions

of start-up companies, while steady, haven't skyrocketed. That has left venture

capitalists with many companies they funded sitting in their portfolios, generating

no returns.

So some venture financiers have started selling off partial stakes in their start-up businesses to private-equity firms, which generally buy and sell more mature businesses, often buying out publicly traded companies. Others are selling their investments to so-called secondary investors who specialize in buying assets from the venture community.

Still other venture capitalists are using their clout to pressure the boards of companies they have invested in to issue them cash dividends as a form of return. Some venture capitalists are going as far as asking start-up executives to buy them out altogether. Venture financiers typically have clout with the companies they invest in, but they must get the board to agree.

"There's a shift going on," says Tom Crotty, a venture capitalist at Battery Ventures, which has offices in Waltham, Mass., and Menlo Park, Calif. "We have to think more creatively."

Battery recently decided to use some of an $850 million venture fund that

was closed to new investors in 2000 to invest in companies that would generate

returns not through an IPO or sale, but by issuing dividends -- a first for

Battery.

Battery in 2003 invested $9.5 million in Made2Manage Systems Inc., part of a $30 million buyout of the company that also included debt. The Indianapolis software company soon paid two cash dividends to Battery totaling $1.25 million.

When Made2Manage took on $15 million of new debt in 2004, it used some of the cash to pay off loans, and Battery got another $10 million payout. In late 2005, Battery sold nearly half its stake to private-equity firm Thoma Cressey Equity Partners. That deal, which involved Made2Manage taking on more debt, produced $48 million in profit for Battery.

The upshot: Just 2½ years after investing in Made2Manage, the company had generated nearly $60 million for Battery -- more than five times what the firm had originally invested, and it still owns a 60% stake.

"When we embarked on the Made2Manage project, the IPO market was nonexistent, and the mergers-and-acquisition market was pretty dormant," says Dave Tabors, a Battery partner who oversaw the investment. "It was a very conscious decision to seek returns differently. Fortunately, the math worked."

The pressure on venture capitalists to creatively translate their investments into profit these days is intense, because venture funds typically are structured to generate returns over 10 years. Those who invested in the late 1990s are eager for a payout.

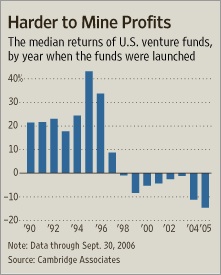

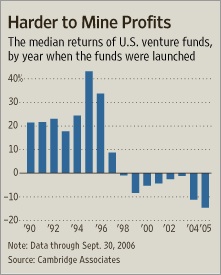

U.S. venture funds launched in 2000 have delivered a median loss of 5.27%, and those launched in 2001 have had a median loss of 4.27%, according to research firm Cambridge Associates. In contrast, U.S. venture funds started in 1995 benefited from selling companies and taking start-ups public in the go-go years of 1999 and 2000, producing median returns of more than 43%, says Cambridge.

Drew Lanza, a general partner at Morgenthaler Ventures in Menlo Park, says the firm has taken dividends from one of its start-up businesses, and adds that he is talking with two others about having them buy out the firm's stake -- for five to 10 times its original investment.

"Historically, I wouldn't do something like this, because I could do better [via] an IPO," Mr. Lanza says. "We're truly feeling our way at this point."

The buildup of start-up companies in venture capitalists' portfolios has proven to be a boon for private-equity firms and secondary investors, including Saints Ventures of San Francisco and W Capital Partners of New York. Both buy stakes in companies that the venture financiers no longer have the patience to own, often for less than the original backers might have wanted.

Ken Sawyer, a managing director at Saints, says he positions his firm as providing a cash-out alternative for venture capitalists. In 2006, Saints bought stakes in 79 companies from venture capitalists and financial institutions.

Atlas Ventures of Waltham is one firm that has sold to secondary investors. In 2004, as the firm finished raising money for a new venture fund, two of its older funds still owned stakes in six life-sciences companies that needed more nurturing.

"Given the age of those portfolios and all the fresh money, we felt our efforts should be going into fresh investments," says Jean-Francois Formela, an Atlas partner.

Atlas sold its stakes in the six life-sciences companies to a Swiss secondary investor called Omega Fund. "It's convenient to find people who are willing to come in and pay something to take these companies off your hands," Mr. Formela says. "We said, 'Let's get rid of those companies.'"

Write to Pui-Wing Tam at pui-wing.tam@wsj.com