WHAT'S HOT AND NOT

WHAT'S HOT AND NOTBy KAREN RICHARDSON

Staff Reporter of THE WALL STREET JOURNAL

August 30, 2004; Page C3

A cash cow of nearly $600 billion grazes in plain sight of U.S. companies, but still eludes many of them.

That cash, often tied up in unpaid customer bills or stale inventory as "working capital," could in many cases be put to better use for, say, paying off debt or creating new products.

"There's cash just waiting there to be liberated off the balance sheet," says Stephen Payne, chief executive of REL Consultancy Group, which helps companies improve cash flows and prepares an annual report on working capital levels. REL's new report, which surveys 1,000 U.S. companies across 69 industry sectors and compares their working-capital levels from 2000 to 2003, will be published Wednesday on CFO.com, the online arm of the trade magazine for financial officers.

WHAT'S HOT AND NOT

WHAT'S HOT AND NOT

A look at how different investments did last week.

Working capital is what companies use for everyday business. Typically defined, it's cash plus money owed by customers and inventories minus payroll, money owed to suppliers and short-term debt costs. Ways to improve working capital -- that is, make more cash available -- include doing a better job of collecting payments. The freed-up funds can be used to repay creditors, invest in research and development or pay dividends to shareholders.

So what would the $590 billion tied up in excess working capital that REL found mean to all those companies? Based on 2003 figures, those companies could have cut net debt for the year by 36% or boosted net income by 9% or even improved return on capital employed -- a common measure of profitability -- by as much as 16%, says Marc Loneux, financial analyst at REL, who helped compile the report.

European companies, meanwhile, have been doing a better job of managing their balance sheets and are catching up to U.S. firms, REL found.

Take Dutch telecommunications company KPN Koninklijke NV, for instance, which went on a mission to free up cash from the balance sheet. KPN had racked up more than $24 billion in long-term debt in 2000 to buy wireless licenses and mobile-phone operations. Last year, KPN cut its working capital by $2.6 billion and reduced its debt to just over $11 billion, according to financial database Capital IQ. In the second quarter of this year, it further cut its working capital by $103 million and reduced its debt to about $10.8 billion. All that debt reduction in turn pulled up the company's sub-investment credit rating, meaning that its future funding costs will be more manageable.

Sometimes cuts in working capital come from unrelated strategic decisions

rather than an effort to better manage the balance sheet. Clothing and toy

retailers, for example, worried about getting whipsawed by fads that can render

new products obsolete, become more careful about building up massive inventories

that tie up working capital.

Apparel chain Gap Inc. greatly reduced its working capital last year by slashing the number of days clothes are stored as inventory by 24% and picking up the pace of bill collections.

U.S. companies' days of inventory outstanding, or the average number of days' worth of sales held in inventory, fell across all industry sectors last year by an average of 2.5% to 31.2 from 2002, according to REL. Days of sales outstanding, or the average collection period, edged 2.6% lower last year to 52.1, reversing a 0.6% rise in 2002.

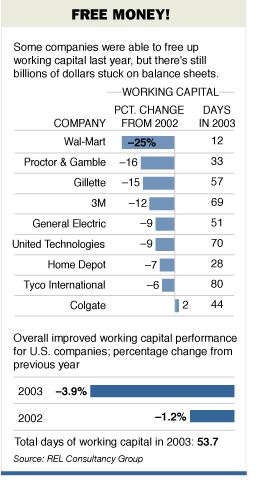

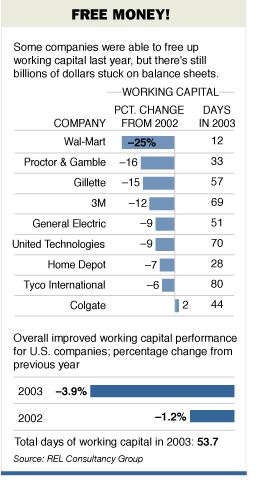

Overall, days of working capital -- the average number of days cash is tied up in these functions -- fell 3.9% to 53.7. That's better than 2002, when the average dipped just 1.2%.

An increase in working capital doesn't necessarily mean a company is doing a poor job of managing its finances or being sloppy with its business. For example, some companies make the strategic decision to get more shelf space for their products, so they tie up more money in working capital by extending payment schedules for customers in new markets.

And this year, economic recovery could encourage companies to focus more on growth, which could require more working capital, Mr. Loneux says.

Some big U.S. companies -- including Wal-Mart Stores Inc., personal-products maker Gillette Co., industrial manufacturer General Electric Co. and computer maker Dell Inc. -- continue to reduce working capital by improving supply-chain, logistics and payment systems.

Wal-Mart, the world's biggest retailer, cut its average collection period by 47% last year to two days, its average days in inventory by 4% to 38, and its average days in working capital by 25% to just 12, REL says. By contrast, bulk retailer Costco Wholesale Corp. was only able to cut down its days in working capital by 3% to seven, even though it reduced its days in inventory by 3% to 29. At the same time, Costco extended its average collection period by 7% to five days.

Sectors that showed deterioration last year in working-capital performance were containers and packaging, medical devices and supplies and pharmaceuticals. REL attributed the problems largely to more competition within the sectors.

Write to Karen Richardson at karen.richardson@awsj.com