|

|||

|

|||

A business can raise its funding from debt or equity, with two key differences setting them apart. The first is the nature of their cash flow claims, with debtholders getting first claim on contractually set cash flows (interest payments, principal payments) and equity investors getting the residual claim of whatever cash flows are left over. The second is control, with debtholders allowing equity investors to make key decisions on what to invest in, where to raise additional funding and how much to pay out in dividends/buybacks. It is not surprising that equity investors make decisions that sometimes further their interests at the expense of bondholders, and that bondholders try to stymie this with restrictions (covenants) and by adding protective features to the bond (conversion, for example).

Sears has a long and storied history in retailing. It revolutionized and dominated the catalog sales business and it stores have been part of the American landscape for decades. Starting about three decades ago, the company found itself squeezed by discount retailers (WalMart and KMart) on the one side and department stores and specialty retailers on the other. That squeeze became more acute when online retailing began to encroach, especially with the growth of Amazon. By 2007, it was clear that Sears was on a long and painful path to irrelevance or worse. Eddie Lampert, an activist investor, became the largest stockholder in Sears with the clear intent of making it a smaller and perhaps more viable business, while closing stores and cutting costs. In particular, he believed that the company's real estate holdings (leased and owned space under stores) could be put to more valuable use.

The Great Sell off

Over the last few years, Sears has been selling off or spinning off portions of its business. In the process, it has changed itself as a company. As this story from the Wall Street Journal suggests, this slimming down of the company has been accomplished by removing its safest and most lucrative assets from its holdings.

http://online.wsj.com/news/articles/SB10001424052702303847804579479761163361186

But the bad news is that it may be running out of the 'good" stuff to sell.

http://blogs.marketwatch.com/behindthestorefront/2013/05/24/with-sears-looking-to-sell-more-assets-what-will-be-left/

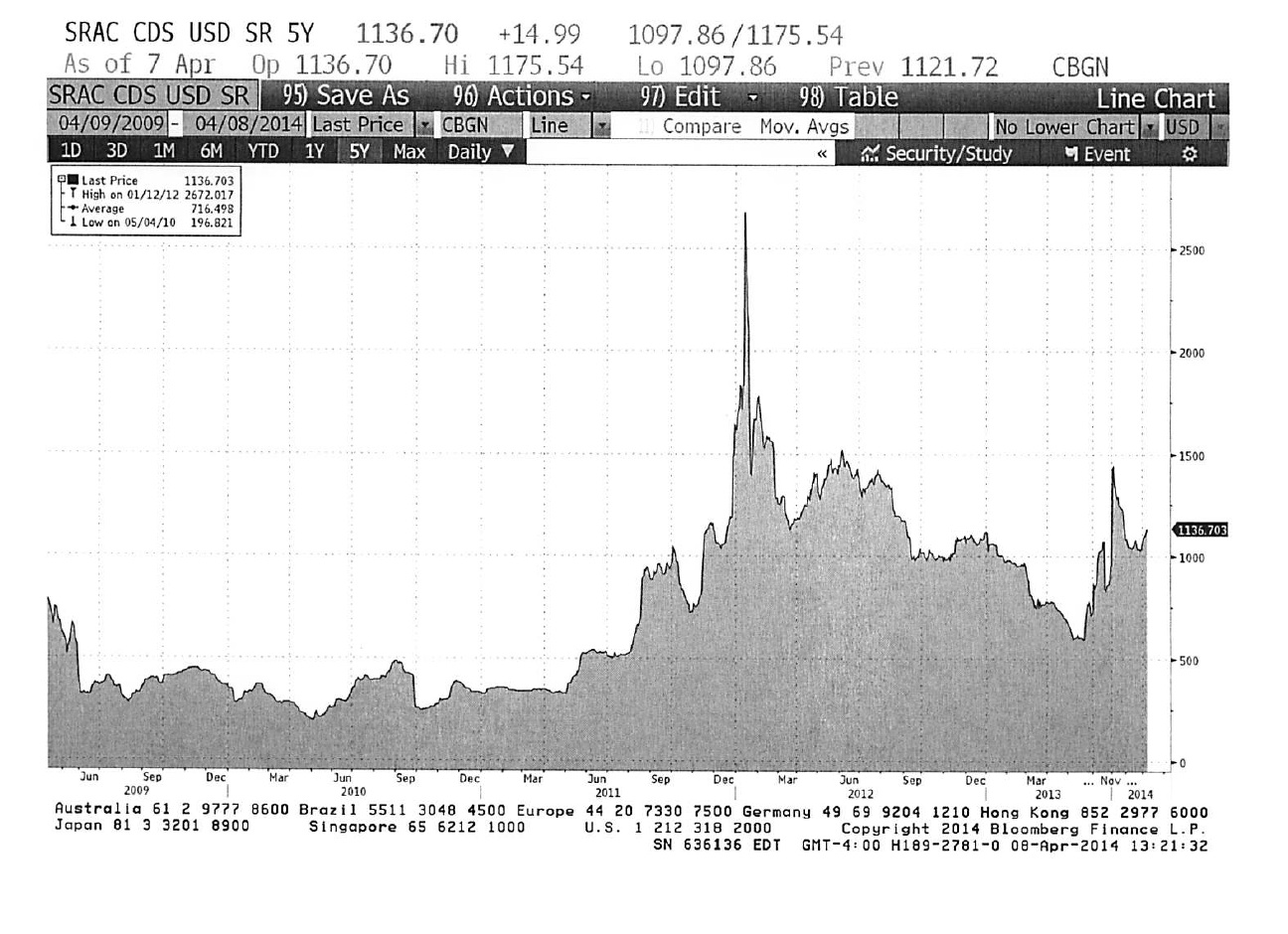

In the process, the company has become riskier to its bondholders as evidenced by the changes in the default spread (at least as measured by the CDS market) on Sears over the last five years:

While equity investors may have benefited from these sales, it is unclear that they have much to crow about either, as shown in the stock price graph below:

And Mr. Lampert is not becoming more popular among company employees.

http://www.huffingtonpost.com/2014/04/05/worst-ceos_n_5097704.html

In short, this is a company where no one is smiling at the moment.

Key Questions